While she grew up on her family’s dairy farm in Hadley and enjoyed that lifestyle, Denise Barstow Manz had no intention of making the 200-year-old operation a career.

“The farm was a place that was fun, and I had a really good time playing with my cousins, being around large animals, and being around nature — it was an amazing way to grow up,” she recalled. “And then, as I got older and I started to see the numbers and realized that the farm was a lot of hard work and not an easy path to wealth, I thought that maybe I should go and do something else.”

She attended the University of New Hampshire — in part because of its renowned dairy program, although she chose a different major — and would later move west and work for the National Park Service, with stints at Yellowstone and Glacier National Park in Montana. And it was while on these assignments that she began to rethink what she would do with her life — and why.

“It finally hit me when I was in Glacier,” she said. “I was a trail guide, and I saw these people donating money to preserve these places. And I thought, ‘if everyone’s giving to places like this, who’s taking care of the places we come from?’ I thought about who was taking care of the place I came from that has been in my family for more than 200 years — and I wanted to be part of that story.”

And with that decision, Barstow Manz would also become part — and she stressed that word part early and quite often, because this is truly a family affair — of one the region’s more intriguing business stories: Barstow’s Longview Farm.

“This is a good place to raise a family in a multi-generational business — everyone can see how life works; the goal has always been to leave something for the next generation.”

It’s a story that includes most of the elements shaping the growth, evolution, and resilience of the local economy today. That list includes entrepreneurship, innovation, technology, clean energy, tourism and hospitality, and sustainable agriculture.

They all come together in an impossibly beautiful, picture-postcard setting, the historic Hockanum Village, framed by the Connecticut River and the Holyoke Range, scenery that belies the myriad and ever-more severe challenges facing dairy farmers — and all those in agriculture — today.

It was these challenges — and especially very trying times roughly two decades ago that prompted the sixth and seventh generations of the Barstow family to take the motto that has defined this business — ‘looking forward since 1806’ — to new dimensions.

Evolution and diversification have been hallmarks of Barstow’s Longview Farm since 1806.

Indeed, a family that has always embraced change and diversification (much more on that later) has taken some dramatic new turns in recent years, first with Barstow’s Dairy Store and Bakery, and later, through a partnership with Vanguard Renewables to build one of the first farm-powered anaerobic digesters in New England. Meanwhile, the 450-acre dairy farm produces 19,000 pounds of milk daily and is a member of the Cabot Creamery/Agri-Mark Cooperative; almost all of the farm’s milk is supplied to the Cabot/Agri-Mark facility in West Springfield and is made into Cabot butter and other products.

The anaerobic digester (AD), installed in 2013 and expanded in 2016, converts cow manure — the herd at the farm produces some 9,000 tons of it annually — and food waste into electricity, heat, and fertilizer.

It has become an important revenue source for the farm, but it also makes a statement about what the sixth and seventh generations of this family — and those that came before them — stand for.

“The AD speaks to what we believe in as a family — that we need to lower our carbon footprint and play a role in mitigating climate change,” Barstow Manz said, adding that, for this family, sustainability comes in many forms and means many things, including work to ensure that this business will be there for the next generations.

Her father, David Barstow, director of special projects at the farm, agreed. He said that, while many things have changed at this location — in general, but especially during his lifetime — what hasn’t changed is that concept of preserving, and persevering, for those who will continue the tradition.

“My father and grandfather used to talk about working with horses,” he said, adding that change and advancement are constants on the farm; the key is to embrace that change and be at the forefront of it. “This is a good place to raise a family in a multi-generational business — everyone can see how life works; the goal has always been to leave something for the next generation.”

“We got together as a family and decided that we needed to either diversify or get out of farming completely.”

All of the various components of Barstow’s Longview Farm make for an intriguing tour — one that usually includes lunch on site — and Denise and other family members offer many of them, all year long. More than that, these elements collaborate to create an inspiring new chapter to a story that began when Thomas Jefferson was patrolling the White House — and even a century before that, as we’ll see.

Herd It Through the Grapevine

They call it Pasture Day, and it is celebrated the first Saturday in May.

As that name suggests, this is the day when the cows, which have spent the winter in barns, get to head back into the pasture. It’s the unofficial start of spring, and a community event — many visitors, including several families living in the area, will come out, watch the heifers celebrate their first taste of fresh grass, enjoy live music, and have some ice cream.

An aerial view of Barstow’s Longview Farm in the historic Hockanum Village.

“People kick up their heels and have a good time; they sit on the hill and watch,” said Barstow Manz, who doesn’t have a formal title, but serves as the farm’s marketing director. She also handles the farm tours, manages the dairy store and bakery, handles outreach, and acts as the main grant writer. She used to feed the calves, but the farm now has an automated calf feeder, one of many examples of innovation at this institution.

She said Pasture Day is just one of the many traditions that have lived on at this property since Septimus Barstow, originally from Wethersfield, Conn., acquired the property on the bank of the Connecticut River that was first farmed at least 100 years earlier by the Lyman family.

Originally a crop farm that focused on asparagus, as many farms in Hadley did, as well as squash, corn, tobacco, and other staples, the Barstow’s operation eventually evolved into a dairy farm after the advent of refrigeration, which provided an avenue for selling milk wholesale.

By the 1930s, dairy was the primary focus at the farm, she went on, adding that, with a herd of 300 cows, this is small to mid-sized operation, one that is dwarfed by huge operations in this country and overseas.

It’s one of a dwindling number of dairy farms both in Massachusetts and across the U.S., she said, citing statistics showing that this country loses five dairy farms every day.

“And when you lose those farms, you’re losing a lot,” she went on. “You’re obviously losing food and food security for that community. But you’re also losing open space, which is good for wildlife habitat, groundwater, climate resilience, and food security. And you’re losing that heritage and that connection to your past.”

The reason for such attrition is simple. This is a very difficult business to be in, she said, adding that the federal government controls milk prices, and margins have historically been paper-thin.

“Even though it’s very perishable, milk is marketed on a global scale, so we’re competing against New Zealand, we’re competing against California … and it’s kind of a broken system,” Barstow Manz explained. “The only real way for dairy farmers to make more money is to make more milk, which doesn’t always line up with demand. And we have no control over the price of the product we produce.”

There are only 115 dairy farms left in the Bay State, and there probably wouldn’t be any were it not for the Massachusetts Dairy Tax Credit, which enables them to remain competitive, she said, adding that there are six operations in Hadley alone, a concentration that testifies to the quality of the soil in that region.

In the early years of this century, the milk market essentially collapsed, primarily because of oversupply, she said, calling this a scary time for the Barstow farm and all the others in this market.

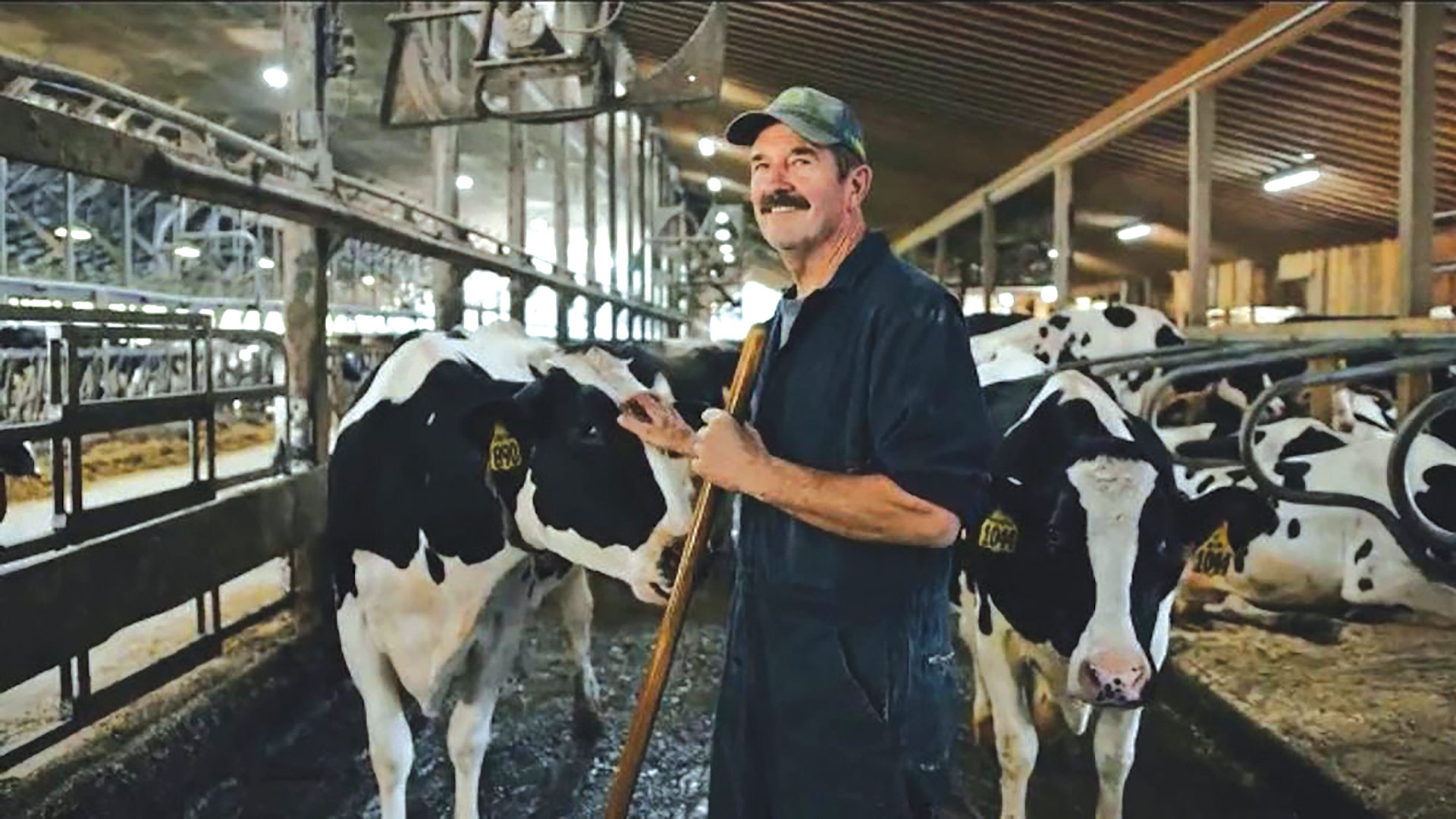

David Barstow says his family lives by the farm’s motto, ‘looking forward since 1806.’

“The milk market crashed like no one had ever seen or felt before in this country; we were getting $12 per hundred pounds of milk, when our break-even was $22,” she explained, adding that it was a critical time in the history of the farm, or another critical time, to be more precise.

“We got together as a family and decided that we needed to either diversify or get out of farming completely,” she recalled. “And that’s when we started talking about how we wanted to diversify and who we wanted to include. And we knew that we wanted to be thoughtful of what the next generation was interested in doing and what our strengths are.”

A Process of Evolution

Over the next several years, diversification would come in several forms, starting with the dairy store and bakery in 2008, an operation inspired in many ways by Denise’s cousin, Shannon Barstow, who does most of the baking. It’s an operation that would transform the farm into a true destination.

“We’re always trying to be mindful and committed to what’s going to be best for our herd, and also for our land, our workforce, our community, and our food system.”

“We understood that people were going to have to drive here if we were going to get the support and the revenue we needed,” she recalled. “So we did lunch, and we started probably too big for our britches. But we’ve definitely settled into who were are, and we have a really supportive community.”

The dairy-store operation and bakery offers both breakfast and lunch as well as a number of prepared foods — and ice cream. The bakery serves up pies, cupcakes, brownies, turnovers, croissants, scones, muffins, breads, and much more. The facility handles private functions, porch parties, and catering. Meanwhile, visitors can buy Barstow’s beef — everything from tenderloin steaks to ground beef — on site. There’s even a drive-thru for those who want or need to grab and go.

The facility draws visitors from around the corner, but also from across the state and beyond, said Barstow Manz, adding that it has become a real destination and a way to take the Barstow name and products well beyond Hadley.

“Most of our regulars are from Hadley and South Hadley,” she explained. “But we have people who come to us from Eastern Mass. because they love our beef, and from the Berkshires because they love our pies; we draw from all over.

Shannon Barstow does most of the baking at the dairy store and bakery, which opened in 2008.

“We opened this place to save the family farm, and it’s had so many other amazing qualities to it that we didn’t really expect,” she told BusinessWest. “It’s become this time capsule for all these family recipes — most of the stuff that’s in the dairy case is Grandma [Marjorie] Barstow’s recipes. And it’s also a neighborhood gathering space — it’s a space where people can work close to home and also be part of a family farm and a local economy on a small scale.”

Indeed, the dairy story and bakery now employs 15 people and has provided many area young people with their first jobs.

The anaerobic-digestion system, launched at a cost of roughly $6 million, is not a supplier of jobs, but it is, as noted earlier, a supplier of electricity, heat, fertilizer — and also pride for a family that has, through its long history, been innovative.

The conversations about installing such a facility began around the same time the family was opening the dairy store and bakery, she said, adding that the system is another important step toward diversification.

Explaining how it works, she said the system takes the energy potential (methane) out of cow manure and food waste and converts it into enough electricity to power 1,600 homes. The food waste comes from local food producers, including Cabot/Agri-Mark, Whole Foods, the Coca-Cola plant in Northampton, and local restaurants.

The food waste and cow manure, both treated and in liquid form, are put into the digester, which Barstow Manz equated to a large stomach, with the gas from the ‘digestion’ process rising to the top of the nine-story facility. That collected gas combusts in an engine and turns a generator, thus creating electricity.

Heat, one of the byproducts of this process, is used to heat that system, provide hot water in the barns, and heat the eight homes on the property, she went on.

“It’s pretty cool that the system has lessened our reliance on fossil fuels as a business, but also on a personal level in our own homes — we don’t have to pay for oil anymore,” she noted. “We’re also getting a chemical-free fertilizer; that’s because most of what we put in we get back; we just need the gas.”

Like the dairy store and bakery, the AD, the second such system in the state and one of the first in the nation, is a reliable revenue stream at a time when such sources of income are needed in the wake of those razor-thin margins in dairy farming, she said, adding that it became reality through partnerships, such as the one with Vanguard Renewables, and grants from several entities, including the Natural Resource Conservation Service, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources, the Center for EcoTechnology, and other entities.

A Butter Alternative

Looking ahead, Barstow Manz said she and others working at the farm have a simple mission — to live up to their motto and continue looking forward.

“We’re always trying to be mindful and committed to what’s going to be best for our herd, and also for our land, our workforce, our community, and our food system,” she said. “Among the dairy farms I’m aware of, we’re been pretty open to accepting new technology and trying new things. We’re always reading and learning and talking to our vets and to our soil agronomists about what we can be doing better.

“I also think it’s cool that the sixth generation has always been focused on the seventh,” she went on, “and the four of us that work here are constantly thinking about what we’re going to leave our kids — what’s in it for the eighth generation.”

If history is any guide, it will be something that can grow and thrive and be sustainable — in every way imaginable.